UIT Helps School of Earth Tap On-Campus Fiber Network for Seismic Research

Wherever you live and work, you’re surrounded by fiber optic cables — including the ones Stanford University maintains in its communications infrastructure. These glass threads, each as thin as a hair, connect our phones and computing devices to the world. But could they also help us hear the Earth, and even warn of earthquakes?

Biondo Biondi, a professor of geophysics at Stanford’s School of Earth, Energy & Environmental Sciences, thinks so. With help from the University IT (UIT) Infrastructure team, he’s leveraging fiber optic cables buried under the university to track and analyze ground motions.

To transform a fiber optic cable into a seismic sensor, Biondi’s team connects a laser “interrogator” to one end of the cable. The device shoots pulses of laser light down the fiber so researchers can measure how it stretches or compresses as a result of passing disturbances, including seismic waves.

Around the corner, Biondi aspires to use the fiber optic cables that criss-cross the Bay Area to build a vast seismic observatory. Dotted with millions — or even billions — of sensors, he envisions a new tool to help us map traffic, improve the resiliency of buildings and infrastructure, and increase our understanding of fault systems that can cause dangerous earthquakes.

Quakes, quivers, and other motions

Biondi built his first on-campus observatory several years ago after partnering with UIT Facilities Director Erich Snow to install a three-mile test loop of optical fiber beneath the Science and Engineering Quad. The original goal of the experiment was to watch for vibrations caused by earthquakes. But the team discovered they could also detect vibrations from man-made sources, such as cars and trucks. This finding opened the door to other applications.

“If you can identify the waves generated by cars, you can continuously monitor what’s going on because traffic is constant in cities. Potentially you can follow traffic flow, but you can also use the seismic data to monitor the health of roadways and buildings,” Biondi explained.

Building a bigger loop

Recently, the professor told Snow that more powerful monitoring equipment had become available. With that, a much longer cable circuit was needed for the next leg of the project.

“Dr. Biondi already knew we had fiber running to the Redwood City campus. But as we talked about it, I suggested that we also had cables running to SLAC and Research Park,” said Snow.

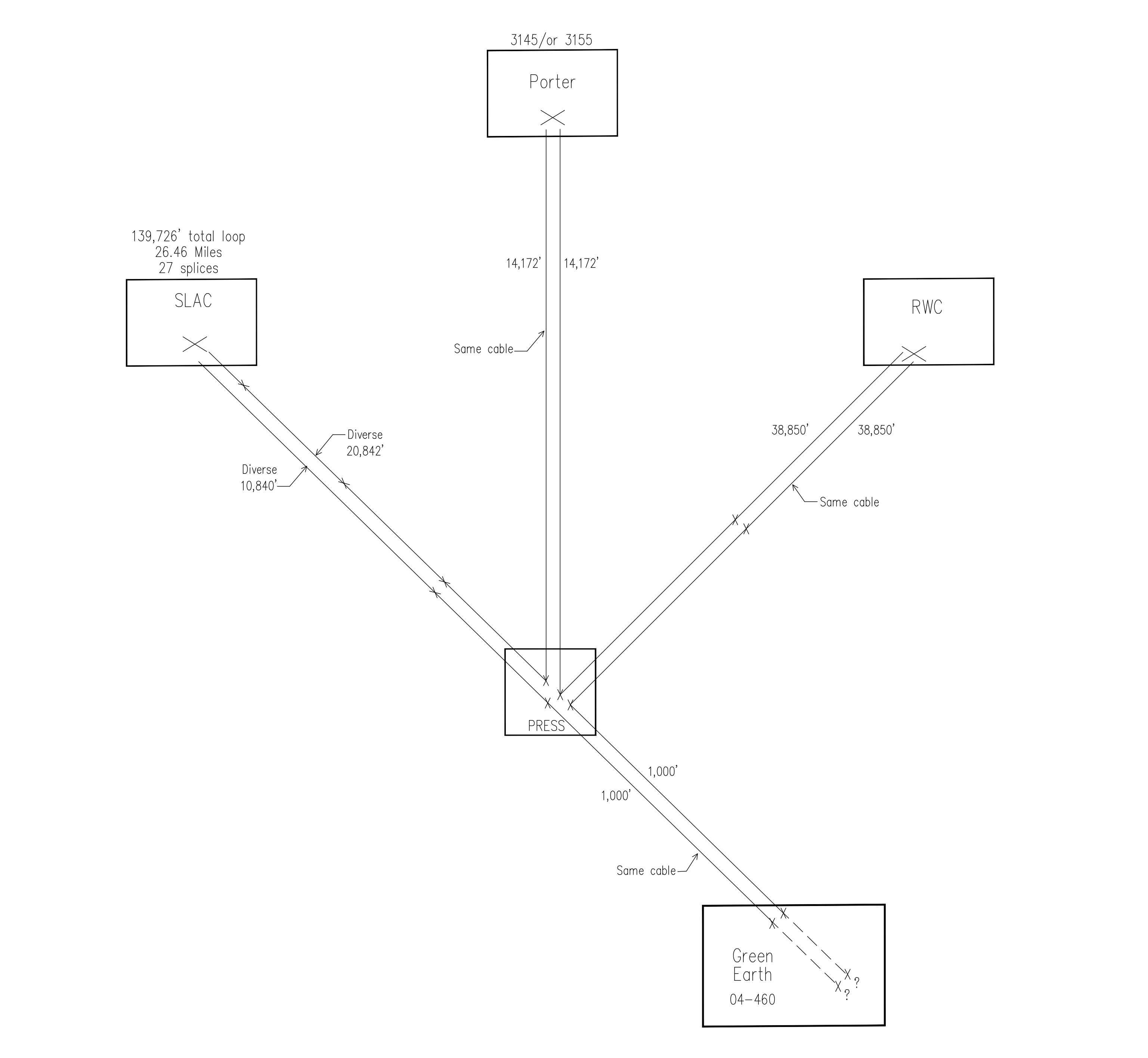

Snow sketched out a 27-mile loop that transverses the historic campus, SLAC, Research Park, and the Redwood City campus. Once the high-level path was mapped, Jim O’Connor and Joanne Valdescona from UIT’s Facilities Engineering team were tasked with identifying the fiber optic cables that could be used to complete the loop and then bring data back to computers in the Green Earth Sciences Building.

Gio Moraga, a technician with UIT Maintenance and Installation, then connected the glass strands end-to-end through a process called fusion splicing. This method melts the two fibers together in such a way that the light passing through the fibers isn’t scattered or lost. Lastly, technicians used an Optical Time Domain Reflectometer (OTDR) to test the integrity of fiber optic cables and provided Biondi with the results.

Biondi said that he appreciated the partnership and noted that his colleagues in UIT were very helpful in creating the greatly expanded circuit. Although he’s just starting to sort through the data, he’s already enthused about the results. He notes that “before we could see the vibrations caused by all the cars passing by, but now we can actually see the waves generated by each, individual car.”

Existing technology, a new application

Using fiber optic cables to check ground vibrations isn’t novel — the military and petroleum industry have done it for years. But Biondi’s work is important because it confirms that cables laid by telecom companies respond to seismic shifts, suggesting an innovative use for these networks.

How might scientists share cables owned by telecommunications and technology companies? The answer is simple: cables used for telecom purposes are a bundle of fiber optic cables encased in a protective skin. Typically, more fiber optic cables than needed are placed in each bundle, resulting in unused “dark fibers.” With Biondi’s technique, the extra lines can be leased for other purposes, such as seismology.

Tapping a low-cost solution

Scientists have traditionally used seismometers to study how the earth moves. But these are expensive to install and maintain. By contrast, fiber optic cables provide a cost-effective solution.

“We have the fiber everywhere in modern cities, particularly in areas like San Francisco, Los Angeles, Tokyo, and Mexico City, that are both high tech and prone to earthquakes. The thought is that we can turn the telecom cables into sensors to monitor seismic activities in the subsurface and better understand the geology under the cities,” said Biondi.

And the dense network of fiber optic cables already in place offers an opportunity to observe an entire seismic wavefield. Because of this, Biondi believes that in the longer term, this approach may help us see the potential for earthquakes in a way that that conventional seismometer, with their limited availability, cannot.

Before meeting with Biondi, Snow said he never thought about how the fiber optic cable could pick up minute ground tremors.

“We never thought about looking at what goes across the glass and how it interacts with the environment. Seeing our fibers used for research in this way has been really interesting,” said Snow.

DISCLAIMER: UIT News is accurate on the publication date. We do not update information in past news items. We do make every effort to keep our service information pages up-to-date. Please search our service pages at uit.stanford.edu/search.

What to read next:

New Resources for Using AI Code Assistants With AI API Gateway

Important Changes to Slack Email Functionality